[Our guest preacher was our Dir. of Music, William Davies. For more information about him, click here: Music. The audio (available below) includes an opening of the sermon not included in the text. It also is much longer than the sermon actually was, as it was left on through the end of the service, so you are able to listen to the post sermon service if you like.]

[Our guest preacher was our Dir. of Music, William Davies. For more information about him, click here: Music. The audio (available below) includes an opening of the sermon not included in the text. It also is much longer than the sermon actually was, as it was left on through the end of the service, so you are able to listen to the post sermon service if you like.]

September 16, 2018: I am struck this morning by the twin themes of speaking and hearing in the Epistle and the Gospel. And those themes lead me to the power – both creative and destructive – of words.

I want to begin, though, with open secrets, things that are, in a sense, unsaid, but loudly understood. We’ve heard a lot about open secrets over the past couple of years. Harvey Weinstein’s abuse of women, it has been reported, was an open secret in Hollywood. Somehow everyone knew about it, but most professed to “know” only in the sense of having heard rumors or second-hand stories. Of course the victims had first-hand knowledge, and it appears others did, too, some even having facilitated Weinstein’s assignations.

More recently, we’ve been hearing reports about former Newark Archbishop Theodore McCarrick, who later became Cardinal-Archbishop of Washington, one of the premier sees of the American Roman Catholic Church. “Everyone knew,” it is said, about his trips to the Jersey shore with seminarians. In this case, I have to admit that, having taken some classes at the seminary at Seton Hall when “Ted” was in Newark, I understand the vague rumor phenomenon. One hears things, but rarely from the voice of direct experience. But again the victims had first-hand knowledge, and others whose actions might actually have mattered seem also to have known quite a bit. Perhaps a culpable bit.

Still more recently, we’ve had the famous New York Times op-ed by an anonymous Trump administration official, and, more substantively, the bombshell of a book by reporter Bob Woodward on the functioning (or not) of the White House. Reaction by senators and congressmen to the revelations in these, and other, sources has often been, “Well, there’s nothing here that everyone in Washington doesn’t know already.” An open secret, and one that leaves us wondering about the ethical course of action for “everyone in Washington” who “already knows.”

As a very open political junky, I’ll just say that I can think of nothing more fun than to kick around these stories just for the sake of exploring their significance, their social and political fallout, and yes, the all-consuming “WHAT DO THEY MEAN FOR THE MIDTERMS???!!!!” question. But I have other forums in which to indulge that impulse.

Here, I want to circle back to what we hear and what we say, now in the context of another open secret.

One of the hallmarks of the Gospel of Mark is the so-called “Messianic Secret.” You will have noticed, over the last weeks, that every time Jesus does something that suggests to the crowds that he is not an ordinary man, he implores them to tell no one what they’ve seen. Of course they immediately proceed to tell everyone what they’ve seen. An open secret.

This morning’s Gospel reading takes the secret further. Here, the disciples are asked, “Who do people say that I am?” That is, Jesus pressed the issue. “C’mon. How would you identify the meaning of what I’ve been doing for my essential identity?” First, they rattle off what appear to have been speculative identities among those who witnessed Jesus’s miracles – John the Baptist, Elijah, a prophet. Then Peter nails it, “You are the Messiah.” After which the messianic secret kicks in and Jesus orders them sternly not to tell anyone.

Which is just as well, because Peter’s correct answer is in fact a misunderstood one. By “messiah,” Peter seems to mean the widely anticipated figure who would gloriously liberate Israel from Roman rule. Wrong. Jesus goes on to instruct Peter and the others about the suffering messiah, a concept that would be, in the context of the culture, a contradiction in terms.

So, Peter and Jesus have both used the same word – revealed, as it were, the same secret – and yet they mean very different things by what they have said.

Which brings me back to hearing and speaking, and, in turn, to James.

But before I get properly to James, I’d like to call to your attention the 17thcentury Puritan theologian John Flavel. The word “Puritan” has a bad odor, suggesting as it does in the popular imagination a group of people whose major religious concern was that no one anywhere have any fun, ever. Not really. While the Puritans were certainly Calvinists, and thus burdened with predestination and a hefty sense of sin, they also wrote some remarkable theology and philosophy. Many writers believe, for instance, that the New England Puritan Jonathan Edwards remains the most original and brilliant philosopher America has ever produced. So: John Flavel. Flavel developed an interesting theory around final judgment and salvation. He suggested that one’s judgment by God would not be complete until all the implications of one’s words had played out among the living. Think about that: What you say gets judged not just as a matter of its truth or falsehood, kindness or cruelty and the like. All the human implications of those words are also laid at your feet. It’s a thought that would incline one to think before speaking.

Back to James.

James is at pains to emphasize the evils that can arise from speech. We can tame any beast, he suggests, “but no one can tame the tongue.” Clearly, he’s addressing some specific problem among the early followers of Christ, a group which, it seems, could well have produced its own tell-all books. But he’s also pointing out the power of words and speaking. If the secret of the “messiah” can be so misunderstood by the very people who were looking so earnestly for just that figure, and yet if, at the same time, the reality embodied in the word can be so powerful, we have a sense of the power of words – “restless evils, full of deadly poison,” but also that with which we, “bless the Lord and Father.”

The whole of scripture, of course, is testimony to the power of words. In Genesis, the creation story unfolds at the command of God’s spoken word – “And God said let there be….” Echoing with parallel language the opening of Genesis, the Gospel of John begins by proclaiming, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Fiddle around with the word order surrounding the verb “to be” in that last phrase and you get “God was the Word.”

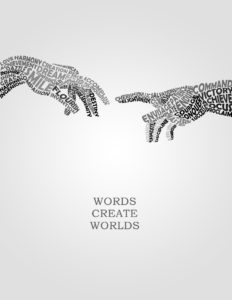

Words, it seems, are powerful things.

The world is awash in words, and very often in words badly used, or even purposefully used to confuse or deceive. Words – words built into sentences and paragraphs; words expressing thoughts, beliefs and convictions – are the things we use to create the world. When we speak words or write words, we help to build, for good or ill, the world our friends inhabit, the world our families inhabit, the world our fellow-citizens inhabit – the world we inhabit. You choose your world with your words.

Open secrets – whether the nefarious ones with which I opened or the messianic one found in Mark – begin in actions. Those actions, though, are rooted in the essential beings of those who act. “Agere sequitur esse” – action follows being – we are told by both Aristotle and Aquinas. We are meant to act on both kinds of secrets, decrying and putting a stop to the actions that are injurious and sinful, and proclaiming the secret of the messiah. John Flavel implies some bad stuff for those who get it wrong.

How we talk about God matters. But it also matters how we talk about the world God has given us, of which we are ongoing agents of creation. It matters because words, like The Word, are a creative force.

One rabbi has written this short meditation on Rosh Hashanah, celebrated just at the beginning of this week.

“In the beginning, G-d spoke and the world came into being.

On Rosh Hashanah, every year, we speak praises and prayers, petitions and pleas. We speak of ourselves and we speak of others…

On Rosh Hashanah, every word we speak counts. Because according to what we speak, and how we speak, G-d speaks.

And accordingly, our world comes into being.”

Amen.

For the audio from the 10:30am service, click below, or subscribe to our iTunes Sermon Podcast by clicking here: