Image by © MAX ROSSI/Reuters/Corbis

[Our guest preacher was Mr. Christopher Dwyer. Christopher is a chorister, co-chair of our Outreach Group, and a seminarian]

July 15, 2018: In the name of the one, holy, and living God: Creator, Christ, and Holy Spirit. Amen.

That Gospel story is a real barn-burner, huh? It’s got everything – sympathetic prisoner of conscience, courtly intrigue, scheming, murder, and dancing, all presented in an opulent court at a decadent party. It’s like something right out of Game of Thrones. Well, more likely, Game of Thrones is right out of this, but I’ll leave that to the pop culture scholars.

I once saw the opera based on this story: Salome, by Richard Strauss. It’s a gorgeous opera, with the complex, bombastic music typical of late romantic composers. My ex-wife and I were in Berlin for New Years, and saw it was playing at the Staatsoper, so we went on a whim. The opera is, well, let’s just say it’s different than the Gospel narrative. The source material is a play by Oscar Wilde, who takes some substantial liberties with the biblical text, and by the time Strauss gets a hold of it (he did his own libretto), the story has become that of a young princess whose unrequited love of a stodgy, moralizing prophet has driven her to such madness that she performs the “Dance of the Seven Veils” for her father in an effort to convince him to behead this man who won’t succumb to her charms, and when that bloody deed is done, she kisses his severed head, for which she is executed, because it’s not really an opera unless the soprano dies in the end.

On our way out of the opera house, we saw a man hawking newspapers in the lobby, with a picture of the topless Salome from after the seven veils dance right on the front page, because you can do that with newspapers in Europe. I snickered and rolled my eyes and with all the self-righteous condescension I could muster, said it was kind of sad that we saw this tremendous performance, and all they saw was a topless woman. They really missed the point of the whole thing.

Or did they get the point precisely?

Obviously, this Gospel text is designed to be about Herod and John, and tangentially Jesus, but Herodias and Salome (I’ll go with the name from the opera for clarity’s sake) just scream out for attention. So, let’s flip the narrative and look at it from their perspectives.

Herodias has just been shuffled from one man to the next, with no say whatsoever in the matter. But, through a stroke of fortune, she’s been taken by Herod, a very powerful man. She’s safe, and more than that, in a much-improved position herself. Her daughter is also safe, and neither have much allegiance to the man to whom they’re currently tied as wife and daughter. Then here comes this crazy man yelling about how their marriage is against the law. Which – okay, crazy people yell things all the time, but people are actually listening to this one. And Herod doesn’t think this is a problem?

So, what we’re not going to do is blame Herodias or Salome. Even the tiny bit of agency that they have is infinitely more than most women of their day, and that they used it in an act of self-preservation is an important point. But I would like to take a closer look at why it was important that they did what they did how they did it.

The great 1stCentury Jewish historian Josephus wrote about the beheading of John the Baptist, too. In this account, Herod found John a bit too persuasive of a prophet, so he had him imprisoned in secret and then executed. Nothing in there about Herodias or Salome’s involvement at all, who are mentioned in other places in Josephus’s works. Meaning that Mark’s account was created out of whole cloth. Why would he do that? Well, at the very end of the book of Malachi, which, if you have a bible without the Apocrypha in the middle, marks the end of the Hebrew scriptures, there is a verse that says “Behold, I am going to send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and terrible day of the LORD.” And, as Mark spends a good deal of time trying to convince people that the “great and terrible day of the LORD” is what Jesus’s incarnation represented, that opened the door for John the Baptist to slide right into the role of Elijah.

And if you’re trying to convince an audience that someone is an Elijah, you’re going to need to give him a strong woman foil, like Elijah had with Jezebel. So, Mark made a Jezebel out of Salome.

Because Jezebel, like Salome, has a legacy attached to her name that far outstrips anything anyone could put in the Bible. She appears precisely once in the Revised Common Lectionary (Year C, Proper 6, track 1, if you’re keeping score at home – and I know you are), but I doubt there’s anyone here who hasn’t heard her name before, even if it’s not directly attached to the biblical figure. To set her biblical context: Jezebel was a Phoenician princess from Sidor, in modern-day Jordan, who married Ahab, the fourth king of Israel after division from Judah. She worshipped Ba’al and Asherah, rather than Yahweh, and encouraged her husband to do the same. In accounts of her life in 1stand 2ndKings, she is shown to be a very powerful political figure, to the extent that even after her son Jehoram was deposed by Jehu, the transfer of power wasn’t complete until her execution.

Jezebel was resolute and fundamentalist in her Ba’al worship, and brutal in her reign. She not only refused to convert to Yahweh, not only converted her husband the king, but also led the wholesale slaughter of Yahweh’s prophets. Later, when Elijah slaughtered Ba’al’s prophets, Ahab told Jezebel about it, and Jezebel put a hit out on him. Then there was this other time, Ahab was feeling a little down one day, and Jezebel tried to cheer him up by expropriating another man’s land through trumped-up criminal charges. Jezebel, not Ahab gave the orders in Samaria.

She was powerful and ruthless and cruel and precisely none of what she did or attained was due to the way she used her sexuality. The sum total of her promiscuity in the Hebrew scriptures? She used red makeup. Twice.

Now, lest we think that our visceral reaction to the name Jezebel is something new, the author of Revelations invoked it like this when talking about a powerful woman of his own he felt the need to slander:

2:20 But I have this against you: you tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet and is teaching and beguiling my servants to practice fornication and to eat food sacrificed to idols. (NRSV)

So, we’re not even done writing the Bible, and we’re already using Jezebel’s name, if not her person, like this.

Why, though? Why do we need Jezebel to be promiscuous? And, besides an easy narrative device to further staple the “Elijah” nametag on to John the Baptist, why did Mark need a Jezebel?

Those questions may be more rhetorical than useful. Let’s try these:

Why does society need to control gender, particularly femininity? and

Why has the Church volunteered to be used as the muscle for this control, practically since our inception?

I was reading a fabulous book about women in the bible in preparation for this sermon, and something the author wrote about Mary Magdalene being confused with other women disciples stuck with me:

“I imagine she wasn’t offended by being thought of as a former prostitute. … And it’s not that she didn’t like being associated with Mary of Bethany’s grief and gratitude. It’s just that it’s not her story.”[1]

And that’s the thing. Even when we strip the judgement away from the sexuality imposed on these powerful women – when we’ve told ourselves that Jezebel just liked to dress up and that Salome was just looking after her mom – we’re still doing wrong by them. We’ve set up these archetypes along the way about good and bad womanhood, and the truth is that none of the archetypes are inherently bad and all women are made in God’s image. But in allowing the society we build to codify these standards, and impose them on women, we’ve taken away women’s ability to tell their own stories. Instead, we’ve told them who they are.

It feels a little too easy to call out our siblings in Christ from the Roman tradition on this topic, but they provide an excellent illustration here.

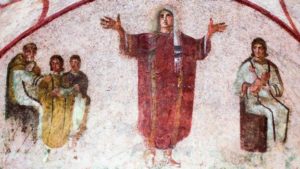

About five years ago, restoration work was finished on some third-century frescos decorating Roman catacombs. In one of these frescos is a picture of a woman in a chasuble, with her hands in the orans position, rather like we’ll see in just a few minutes – or, would, if it weren’t too hot to vest. When questioned about this seeming incongruity between current ordination practices and historical tradition, officials of the Roman church laughed off the idea that pictures of women in chasubles with their hands in the orans position could be indicative of their having once been women priests. For them, the very essence of womanhood left no room for the priesthood. It was, as the philosophers would say, an ontological impossibility – kind of like a contradiction in terms.

I’m not taking a victory lap here – had that been a London catacomb 50 years ago, the same thing would have been said by an Anglican official – but notice what’s happened. A group of men has made a definitive verdict both on the nature of God’s image in woman and God’s sacrament in ordination, and used that verdict to maintain control of both.

And this is why the discussions around liturgy in our church have been so crucial. To whom are we giving the authority to tell our story as a church? This thing we do here on a Sunday morning – this is how we express who we are collectively as the Body of Christ. As Episcopalians. If someone told me they wanted to know more about what it means to be an Episcopalian, the first thing I’d do is invite them to Eucharist. Over coffee, I’d get them a copy of the prayerbook. And if they’d been going for a bit, I’d ask them if they wanted to see something really Anglican and take them to an Evensong.

Of course, they could go somewhere else and ask what it means to be an Episcopalian and hear anything from “Oh, those are the real Frozen Chosen, right?” to “Aren’t they the ones who ordained a gay bishop and are now trying to turn God into a woman?”

Now, take that down one level. Let’s say I convince my friend to go to Eucharist, but that friend doesn’t live in northern New Jersey. Will they be invited to Communion if they’ve never been baptized? Should I try to look up the open table policies of the diocese and church where they’re thinking of going? Should I steer them towards a place that will accept them, or tell them that coexisting in such difference is part of what makes us who we are?

And what if they’re not straight, white, or male? Should I check to make sure they’ll feel comfortable? Do I steer them towards a parish where they might feel more represented? Do I give them the gory history of all of our recent infighting?

All that, and we haven’t even changed the prayerbook yet.

There was a tweet that came across my timeline last night about this. Since getting plugged into Episcopal Twitter more, I’ve found a few priests who tweet out bits of their sermon prep, or sermon angst, as the case may be. This was from Dr. Wil Gafney, an Episcopal priest, seminary professor, and renowned Hebrew Scripture scholar from Fort Worth who’s written a different spectacular book on women[2]in the bible. She’s preaching on the Hebrew Scripture from the other track this week – from 2ndSamuel – but what she said would be of comfort to the women in our Gospel today:

“listen to women, believe us. Believe us about assault and harassment, believe us about discrimination and underrepresentation and overwork and under pay… and believe us when we say the Church’s fixation on masculine language and imagery for God is harmful to us.”[3]

Listen to women.

Amen.

For the audio from the 10:30am service, subscribe to our iTunes Sermon Podcast, or click here:

[1] Alice Connor, Fierce: Women of the Bible and their Stories of Violence, Mercy, Bravery, Wisdom, Sex, and Salvation,(Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2017), Kindle, 169.

[2] Wilda Gafney, Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne,(Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017), Kindle.

[3] https://twitter.com/WilGafney/status/1018261273962778624