October 12, 2014: I can’t hear today’s Gospel passage without remembering a sermon I heard when I was about 5 years old. In those days – this would have been around 1960 – it was fairly common in the Roman Catholic Church for priests from certain religious orders to undertake a sort of preaching mission, traveling from church to church giving what were presumed to be first class sermons (and doubtless doing some fund-raising on the side). The particular sermon to which I’m referring was preached by an Irish Redemptorist priest who was apparently renowned for his ability to raise the roof with his sermons. So, we heard the Gospel read by the pastor of the church, ending of course with the poor dress-code-violating-wedding guest being bound hand and foot and thrown out into the darkness into the weeping and gnashing of teeth. Then the Great Sermon. I don’t remember the whole thread of the sermon’s argument, but I clearly remember its punch line.

“What is the weddin’ garment you’ll be needin’ then?” asked the preacher, preparing to deliver the homiletic coup de gras. The question was clearly rhetorical, and the answer followed quickly:

“Unless you approach the t’rone of God wrapped in the spotless fait’ of Holy Mother the Church, you’ll not being enterin’ the Kingdom of Heaven. No. You’ll be out in the darkness, weepin’ in misery and gnashin’ your teeth with the Protestants!”

If anyone would like to practice weeping and gnashing, please gather directly after this service in the choir room.

My point – aside from the amusement value of the story – is that texts can be problematic. If you’ve been keeping track, you’ll know that we’ve had a string of parables of the Kingdom in recent weeks in which the Kingdom of God has been compared to a vineyard owner whose wicked tenants kill first his slaves and then his son; to another landowner who upsets the usual wage system by paying the laborers hired last the same as those hired first, despite the fact that the latter had worked many more hours; to a king who is merciful to a slave who is in debt to him, but who then turns the slave over to be tortured when the slave himself refuses mercy to his fellow-slave; and of course this morning to the king who, having to quickly populate his wedding feast with guests on the fly, then does a quick about-face, accusing one stunned guest of having failed to dress properly and tosses him out to face an unpleasant fate.

And what do we learn? Many are called, but few are chosen. The kingdom will be taken from some and given to others who bear the fruits of the kingdom. The first will be last and the last first. You’ll suffer too, if you don’t forgive your brother or sister. Some of these phrases have actually become part of everyday speech, yet we’re still not sure what to make of them. Did Jesus really mean to deliver a message which sometimes seems to suggest that the nature of the kingdom and admission to it involves a sort of trick question? Aha! You thought you knew how this worked, but …. Gotcha!

To a certain extent, he did. That is, the passages of the last few weeks are clearly meant to suggest that the assumptions of the “religious people” of the time needed to be upended. By extension, I suppose we should draw the same conclusion: Don’t assume you know who’s in and who’s out, and don’t assume that doing this or that provides much of a guarantee. And CERTAINLY don’t set yourself up as judge of someone else’s worthiness. Passing judgment on what is and is not “Christian” seems like a bad idea in the light of these readings.

All of that is fairly obvious, though. The danger in texts lurks in the fact that – especially when, like these, there’s a lot of analogy involved (the kingdom is like this or like that) – it’s awfully tempting to start viewing them as empty vessels into which we can pour our own meaning. I really doubt that the wedding garment in today’s Gospel was intended as an analogy for correct Roman Catholic dogma. The problem of course is to try to figure out what it is an analogy for without making a similarly egregious mistake of interpretation.

Now, let me turn to another text, very different from the Gospel. It’s the very short text of this morning’s anthem:

I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste.

He brought me to the banqueting house, and his banner over me was love.

These lines are part of a longer passage from the Song of Solomon. You’ll probably recognize them in the context of the whole.

I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valley

As the lily among the thorns, so is my love among the daughters

As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons.

I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste.

He brought me to the banqueting house, and his banner over me was love.

Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples, for I am sick of love.

His left hand is under my head, and his right hand doth embrace me.

I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not

up nor awake my beloved till he please.

Well! It’s becoming a bit steamy in here isn’t it? I’m now imaging the Bible in that rack at Barnes and Noble that holds a raft of romance novels whose jackets always feature a buxom young woman in the embrace of an impossibly fit young man in – or mostly out of – vaguely Victorian attire, suggesting that mid-19th century Dorset was populated not by landed gentry and their deferential tenant farmers, but by plastic surgeons and personal trainers. What are we to make of THIS text?

It’s a dialogue between two lovers – a bride and bridegroom, presumably – extolling each other’s …er, um …”virtues.” So, one could imagine it as a way of expressing the intimate relationship between God and his people. Or one could serve up a helping of Christ as the bridegroom and the Church as the bride. But again, if in a very different textual circumstance, there is that danger that we’re just attaching a significance we like to what is a quite obscure piece of ancient poetry.

A little recap here: We have two pieces of scripture, separated by centuries, one of which suggests a judgmental God who tosses gormless wedding guests into the darkness, and another of which verges on being erotic poetry. And on this basis we are meant to understand God. One does begin to understand religious skepticism.

But there’s music. Anyone who knows me well – and certainly my students – will tell you that I love words. I love reading them, I love pulling their meanings apart, playing with them, writing with them. Texts are fun and often very important. We even have some we call “sacred.” But all texts and every word, even if sacred, has limits. Words express meaning, but they can only contain just so much meaning. “Words,” as we so often admit, ”fail me.” They fail particularly often when we attempt to describe the indescribable.

God is simply bigger than any linguistic capability can comprehend. And because language is what we have to think with, our use of it necessarily limits our understanding of a God who is already beyond our complete comprehension. Even in our survey of the last few Sundays’ Gospels we find a God who is at once apparently capricious and angry, but also merciful and radically devoted to the salvation of his entire creation. In the face of that God, our essential stance is one of awe, of worship. And music is the language of worship. When we encounter God, words fail, but still we are moved to worship. What fills the gap between the incapacities of language and the expression of worship is music. Because it is, in the most literal sense, im-mediate. That is, it requires no intermediary. It speaks directly to our hearts and souls. Because music speaks immediately to our selves, we needn’t venture down the path of analogy or metaphor. We don’t need to figure out “what it means,” and we aren’t tempted to fill it up with the meanings we would prefer. Music is what it means and means what it is.

My partner is fond of chiding me, telling me that I go to church “just for the music.” I of course reply that that’s not true; I also go because they pay me to show up! In a sense, though, he’s right. Even if I don’t go to church just for the music, it’s true that, in my conception, music is an integral part of the language of worship, not merely a pleasant decoration added to liturgical activities that depend upon words. For me, any attempt at a worshipful stance before an ineffable God fails in the absence of music.

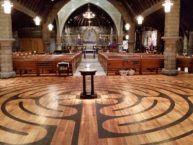

That’s why we need choirs, why – to borrow the title of today’s celebration – we need to appreciate choirs. Because when we do not have the language for worship or for prayer – joyous, reflective, sorrowful, repentant – in whichever mode we encounter it, the choir gives it to us. When our minds refuse to focus on the words we need – because we can’t stop thinking about paying bills, or getting everything done in too little time, or what’s for dinner, or what will happen in the next episode of Downton Abbey; or when we can find words and focus on them, but they are still inadequate to the task of worship and prayer, choirs provide the language of music. Every week and on cue choirs lift us out of the limited world of language and into an entirely different realm – the realm of worship.

“I sat down under his shadow with great delight. And his fruit was sweet to my taste.” As words, they’re a puzzle. As music, they’re worship.